The arts of Zen are not intended for utilitarian purposes, or for purely aesthetic enjoyment, but are meant to train the mind, indeed, to bring it into contact with ultimate reality.

~ D.T. Suzuki

Zen Art

Asian Brush Painting

Asian Brush Painting

Zen Buddhism and Taoism in China used the creation of poetry, painting and calligraphy as spiritual pathways, where engagement in the creative process quiets the mind, thus allowing spiritual insights to be freely expressed. The height of Zen arts in China, particularly painting and poetry, came in 960-1279 C.E. The art being made was not representational or iconographic, it wasn't meant to deepen one's faith or religious experience, nor was it used in worship or for ceremonies. The only goal in Zen art was to reveal the true nature of the artist and reality as it is experienced by the artist. Zen arts became sacred arts meant to transform the way the artist or audience sees or experiences things and what it means to be a living human being.

Over time Zen masters turned to art as a tool for instruction. Monasteries became destinations for artists who sought ways to unite creativity with spiritual cultivation. Zen Buddhism came to Japan in the 13th century and with it Zen arts. Japanese culture at that time, which was focused on the appreciation of nature and the ephemeral, easily integrated Zen arts. To this day, much of what we think as traditional Zen art is based on an aesthetic that's distinctly Japanese. As it had in China, Zen arts in Japan became an inseparable aspect of Zen training. These Zen arts were called the "artless arts of Zen".

In addition to poetry, painting and calligraphy, these "artless arts" included suizen (bamboo flute meditation), karesansui ( landscape gardening meditation), and kyūdō, (archery meditation). Some of the more familiar Zen arts are described below:

Over time Zen masters turned to art as a tool for instruction. Monasteries became destinations for artists who sought ways to unite creativity with spiritual cultivation. Zen Buddhism came to Japan in the 13th century and with it Zen arts. Japanese culture at that time, which was focused on the appreciation of nature and the ephemeral, easily integrated Zen arts. To this day, much of what we think as traditional Zen art is based on an aesthetic that's distinctly Japanese. As it had in China, Zen arts in Japan became an inseparable aspect of Zen training. These Zen arts were called the "artless arts of Zen".

In addition to poetry, painting and calligraphy, these "artless arts" included suizen (bamboo flute meditation), karesansui ( landscape gardening meditation), and kyūdō, (archery meditation). Some of the more familiar Zen arts are described below:

Bonsai

Bonsai

Bonsai, the art of miniature tree sculpting. It may take only five or ten minutes to prune a tree that stands 12 inches high, but it's the contemplation of the tree and its design, which is slowly changing and growing over a long period of time, that's important. The artist contemplates the tree and its shape for many hours and days, before any adjustments are made. It's not unusual that through this contemplation only one or two careful clips are made in a single year. Some bonsai trees are centuries old, outliving the original artist.

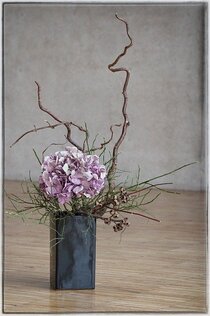

Ikebana (flower arranging)

Ikebana (flower arranging)

Ikebana (also known kadō) is the meditative art of flower arranging and has a strong relationship with chadō, which is a form of meditation through the performance of a tea ceremony.

For the Zen artist, no matter what form of art being practiced, the intention is to bring out through the creative work, as simply and directly possible, the essence of the object. In order for this to be possible, the Zen artist must intimately know this essence through direct experience. All preconceived ideas and concepts must be dropped. While the artist is involved in getting in touch with the object's essence, they are developing techniques and skills through practice and repetition.

Most Zen arts emphasize spontaneity in creating the piece, in order to bypass the intellectual mind. Only a mind that is perfectly clear can hold an object's essence. This essence often requires little complexity to be accurately expressed. With a few swipes of a brush, the artist can depict the sinuous shape of a cat or a range of rugged mountains. This effective subtly can only emerge from the artist's mind attuned to the essence of the object of contemplation.

The practice of the "artless arts" required the discipline to stay with the process of sharpening one's skills and one's understanding of the nature of reality. One key element in the Zen arts is the guidance of a master teacher, as these skills in expression can only come from transmission of the teacher's mind to the student's mind. A powerful bond between teacher and student is necessary in order for the Zen art tradition to be passed down.

Traditional Zen arts cannot be taught through a book or video. The physical presence of the teacher with the student is necessary. The teacher will demonstrate a technique, while the student observes carefully. Then the student will attempt the technique observed, while the teacher observes the student's process. The teacher may make seemingly minor corrections, perhaps the posture of the student, or the angle of the brush in the student's hand. Most of the teacher's instruction is silent, as the emphasis is on direct experience, the living embodiment of the art form, rather than any theory of concept.

One can, however, embrace the essence of Zen art without a teacher. It will not result in authentic traditional Zen art skills, but practicing Zen art techniques can lead to insight into the creative process.